1.7. Lecture 3#

Step through the medical example key#

Some of the answers are straightforward but make sure you agree with your neighbors. We’ll split out a few follow-up points.

Follow-up question on 2.

Why is it \(p(H|D)\) and not \(p(H,D)\)?

Answer

Recall that \(p(H,D) = p(H|D) \cdot p(D)\). You are generally interested in \(p(H|D)\). If you know \(p(D) = 1\), then they are the same.

Follow-up question on 5.

The emphasis here is on the sum rule. Why didn’t any column except Total in the sum/product rule notebook add to 1?

Answer

Because were were looking at \(p(\text{tall,blue}) + p(\text{short,blue}) \neq 1\), whereas \(p(\text{tall}| \text{blue}) + p(\text{short}| \text{blue}) = 1\).

In general and for 6. in particular we emphasise the usefulness of Bayes’ theorem to express \(p(H|D)\) in terms of \(p(D|H)\).

Make sure that 8. and 9. are clear to you. In 8., this is standard but not so obvious at first; after it becomes familiar you will find that you jump right to the end.

Recap of coin flipping notebook#

Recall the names of the pdfs in Bayes’ theoem: posterior, likelihood, prior, evidence; and recall Bayesian updating: prior + data \(\rightarrow\) posterior \(\rightarrow\) updated prior \(\rightarrow\) updated posterior \(\rightarrow\) \(\ldots\).

Take-aways and follow-up questions from coin flipping:

How often should the 68% degree of belief interval contain the true answer for \(p_H\)?

Is the frequentist 1\(\sigma\) interval the same as the Bayesian 68% DoB interval? If so, should they be? If not, why are they different?

What prior would you choose? How does this affect how long it takes you to arrive at the correct conclusion? Note that the answer to this question may be dependent.

What would your standard be for deciding the coin was so unfair that you would walk away? That you’d call the police? That you’d try and publish the fact that you found an unfair coin in a scientific journal?

What if you were sure the coin was unfair before you started? (E.g. you saw the person doctoring it.) What prior would you choose then? What happens to the posterior in this case?

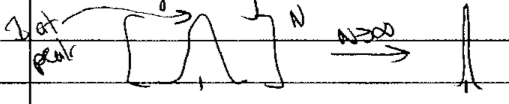

Different priors eventually give the same posterior with enough data. This is called Bayesian convergence. How many tosses are enough? Hit

New Datamultiple times to see the fluctuations. Clearly it depends on \(p_h\) and how close you want the posteriors to be. How about for \(p_h = 0.4\) or \(p_h = 0.9\)?Answer

\(p_h = 0.4\) \(\Longrightarrow\) \(\approx 200\) tosses will get you most of the way.

\(p_h = 0.9\) \(\Longrightarrow\) much longer for the informative prior than the others.

Why does the “anti-prior” work well even though its dominant assumptions (most likely \(p_h = 0\) or \(1\)) are proven wrong early on?

Answer

The “heavy tails” (which in general means the probability away from the peaks; in the middle for the “anti-prior”) mean it is like uniform (renormalized!) after the ends are eliminated. An important lesson for formulating priors: allow for deviations from your expectations.

Case I and Case II for priors both use the beta distribution as a conjugate prior (the uniform case is included as \(\alpha=1,\beta=1\)). From the code for updating:

y_i = stats.beta.pdf(x,alpha_i + heads, beta_i + N - heads)Is there a difference between updating sequentially or all at once? Do the simplest problem first: two tosses. Let results be \(D = \{D_k\}\) (in practice take 0’s and 1’s as the two choices \(\Longrightarrow\) \(R = \sum_k D_k\)).

The general relation is \(p(p_h | \{D_k\},I) \propto p(\{D_k\}|p_h,I) p(p_h|I)\) by Bayes’ theorem.

First \(k=1\) (so \(D_1 = 0\) or \(D_1 = 1\)):

(1.14)#\[ p(p_h | D_1,I) \propto p(D_1|p_h,I) p(p_h|I)\]Now \(k=2\), starting with the expression for updating all at once and then using the sum and product rules (including their corollaries marginalization and Bayes’ Rule) to move the \(D_1\) result to the right of the \(|\) so it can be related to sequential updating:

(1.15)#\[\begin{split}\begin{align} p(p_h|D_2, D_1) &\propto p(D_2, D_1|p_h, I)\times p(p_h|I) \\ &\propto p(D_2|p_h,D_1,I)\times p(D_1|p_h, I)\times p(p_h|I) \\ &\propto p(D_2|p_h,D_1,I)\times p(p_h|D_1,I) \\ &\propto p(D_2|p_h,I)\times p(p_h|D_1,I) \\ &\propto p(D_2|p_h,I)\times p(D_1|p_h,I) \times p(p_h,I) \end{align}\end{split}\]What is the justification for each step?

1st line: Bayes’ Rule

2nd line: Product Rule (applied to \(D_1\))

3rd line: Bayes’ Rule (going backwards)

4th line: tosses are independent

5th line: Bayes’ Rule on the last term in the 3rd line

The fourth line of (1.15) is the sequential result! (The prior for the 2nd flip is the posterior (1.14) from the first flip.)

So all at once is the same as sequential as a function of \(p_h\), when normalized!

To go to \(k=3\):

\[\begin{split}\begin{align} p(p_h|D_3,D_2,D_1,I) &\propto p(D_3|p_h,I) p(p_h|D_2,D_1,I) \\ &\propto p(D_3|p_h,I) p(D_2|p_h,I) p(D_1|p_h,I) p(p_h) \end{align}\end{split}\]and so on.

What about “bootstrapping”? Why can’t we use the data to improve the prior and apply it (repeatedly) for the same data. I.e., use the posterior from the first set of data as the prior for the same set of data. Let’s see what this leads to (we’ll label the sequence of posteriors we get \(p_1,p_2,\ldots,p_N\)):

\[\begin{split}\begin{align} p_1(p_h | D_1,I) &\propto p(D_1 | p_h, I) \, p(p_h | I) \\ \\ \Longrightarrow p_2(p_h, D_1, I) &\propto p(D_1 | p_h, I) \, p_1(p_h | D_1, I) \\ &\propto [p(D_1 | p_h,I)]^2 \, p(p_h | I) \\ \mbox{keep going?}\quad & \\ p_N(p_h | D_1, I) &\propto p(D_1|p_h, I)\, p_{N-1}(p_h | D_1, I) \\ &\propto [p(D_1 | p_h, I)]^N \, p(p_h | I) \end{align}\end{split}\]Suppose \(D_1\) was 0, then \([p(\text{tails}|p_h,I)]^N \propto (1-p_h)^N p(p_h|I) \overset{N\rightarrow\infty}{\longrightarrow} \delta(p_h)\) (i.e., the posterior is only at \(p_h=0\)!). Similarly, if \(D_1\) was 1, then \([p(\text{tails}|p_h,I)]^N \propto p_h^N p(p_h|I) \overset{N\rightarrow\infty}{\longrightarrow} \delta(1-p_h)\) (i.e., the posterior is only at \(p_h=1\).)

More generally, this bootstrapping procedure would cause the posterior to get narrower and narrower with each iteration so you think you are getting more and more certain, with no new data!

Warning

Don’t do that!

Something to come back to: Frequentist point estimates

Maximum-likelihood means: what value of \(p_h\) maximizes the likelihood (notation: \(\mathcal{L}\) is often used for the likelihood)

Answer

Similarly, the standard deviation is \(\sigma = \sqrt{p_h(1-p_h)/N}\).

Gaussian noise and averages#

Let’s work through Parameter estimation example: Gaussian noise and averages I.

Import of modules

Using seaborn just to make nice graphs

Example from Sivia’s book [SS06]: Gaussian noise and averages.

\[ p(x | \mu,\sigma) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}} \]where \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are given and the pdf is normalized (\(\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}e^{-(x-\mu)^2/2\sigma^2} dx = 1\)).

Its justification as a theoretical model is via maximum entropy, the “central limit theorem” (CLT), or general considerations, all of which we will come back to in the future.

\(M\) data measurements \(D \equiv \{x_k\} = (x_1, \ldots, x_M)\) (e.g., \(M=100\)), distributed according to \(p(x|\mu,\sigma)\) (that implies that if you histogrammed the samples, they would roughly look like the Gaussian).

How do we get such measurements? We will “sample” from \(\mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma^2)\).

Goal: given the measurements \(D\), find the approximate \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\).

Frequentist: use the maximum likelihood method

Bayesian: compute posterior pdf \(p(\mu,\sigma|D,I)\)

Random seed of 1 means the same series of “random” numbers are used every time you repeat. If you put 2 or 42, then a different series from 1 will be used, but still the same with every run that has that seed.

stats.norm.rvs(“norm” for normal or Gaussian distribution; “rvs” for random variates) as in Exploring PDFs.size=Mis a “keyword argument” (oftenkw\(\equiv\) keyword), which means it is optional and there is a default value (here the default is \(M=1\)).

Consider the number of entries in the tails, say beyond \(2\sigma\) \(\Longrightarrow\) \(x>12\) or \(x < 8\).

Note the pattern (or lack of pattern) and repeat to get different numbers. (How? Change the random seed from 1.) Always play!

Questions about plotting? Some notes:

We’ll repeatedly use constructions like this, so get used to it!

;means we put multiple statements on the same line; this is not necessary and probably should be avoided in most cases.alpha=0.5makes the (default) color lighter.Try

color='red'on your own in the scatter plot.You might prefer side-by-side graphs \(\Longrightarrow\) alternative code.

An “axis” in Matplotlib means an entire subfigure, not just the x-axis or y-axis.

If you want to know about a potting command already there,

shift-tab-tab(or you can always google it).To find

vlines(vertical lines), google “matplotlib vertical line”. (Try it to find horizontal lines.)fig.tight_layout()for good spacing with subplots.

Frequentist approach

true value for parameters \(\mu,\sigma\), not a pdf

\(\log\mathcal{L}\) for several reasons.

to avoid problems with extreme values

\(\mathcal{L} = (\text{const.})e^{-\chi^2}\) so maximizing \(\mathcal{L}\) is same as maximizing \(\log\mathcal{L}\) or minimizing \(\chi^2\).

Carry out the maximization

\[ \frac{\partial\log\mathcal{L}}{\partial\mu} = -\frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^M 2 \frac{x_i-\mu}{\sigma^2}\cdot (-1) = \frac{1}{\sigma^2}\sum_{i=1}^M (x_i-\mu) = \frac{1}{\sigma^2}\Bigl(\bigl(\sum_{i=1}^M x_i\bigr) - M\mu\Bigr) \]Set equal to zero to find \(\mu_0\) \(\Longrightarrow\) \(M\mu_0 = \sum_{i=1}^M x_i\) or \(\mu_0 = \frac{1}{M}\sum_{i=1}^M x_i\).

You do \(\sigma_0^2\)! (Easier to do \(d/d\sigma^2\) than \(d/d\sigma\).)

Do these make sense?

Note the use of

.sumto add up the \(D\) array elements.Printing with f strings:

f'...'.2fmeans a float with 2 decimal places.

Note comment on “unbiased estimator”

an accurate statistic

Here compare \(\mu_0\) estimated from \(\frac{1}{M}\) vs. \(\frac{1}{M-1}\).

If you do this many times, you’ll find that \(\frac{1}{M}\) doesn’t quite give \(\mu_{\rm true}\) correctly (take mean of \(\mu_0\)s from many trials) but \(\frac{1}{M-1}\) does!

The difference is \(\mathcal{O}(1/M)\), so small for large \(M\).

Compare estimates to true. Are they good estimates? How can you tell? E.g., should they be within 0.1, 0.01, or what? (More about this as we proceed!)

Bayesian approach \(\Longrightarrow\) \(p(\mu,\sigma|D,I)\) is the posterior: the probability (density) of finding some \(\mu,\sigma\) given data \(D\) and what else we know (\(I\)).

\(I\) could be that \(\sigma > 0\) or \(\mu\) should be near zero.

One more time with Bayes’ theorem:

Label each term in Eq. (1.16).

Bayes’ Theorem tells you how to flip \(p(\mu,\sigma|D,I) \leftrightarrow p(D|\mu,\sigma,I)\). Here the first pdf is hard to think about evaluating but the second pdf is easy.

If \(p(\mu,\sigma | I) \propto 1\), this is called a “flat” or “uniform” prior, in which case

and a Frequentist and Bayesian will get the same answer for the most likely values \(\mu_0,\sigma_0\) (called “point estimates” as opposed to a full pdf).

We will argue against the use of uniform priors later.

The prior includes additional knowledge (information). It is what you know before the measurement in question.

Discussion point

A frequentist claims that the use of a prior is nonsense because it is subjective and tied to an individual. What would a Bayesian statistician say?

To the lighthouse!#

Homework: work through Radioactive lighthouse problem.